This essay was written in 2012

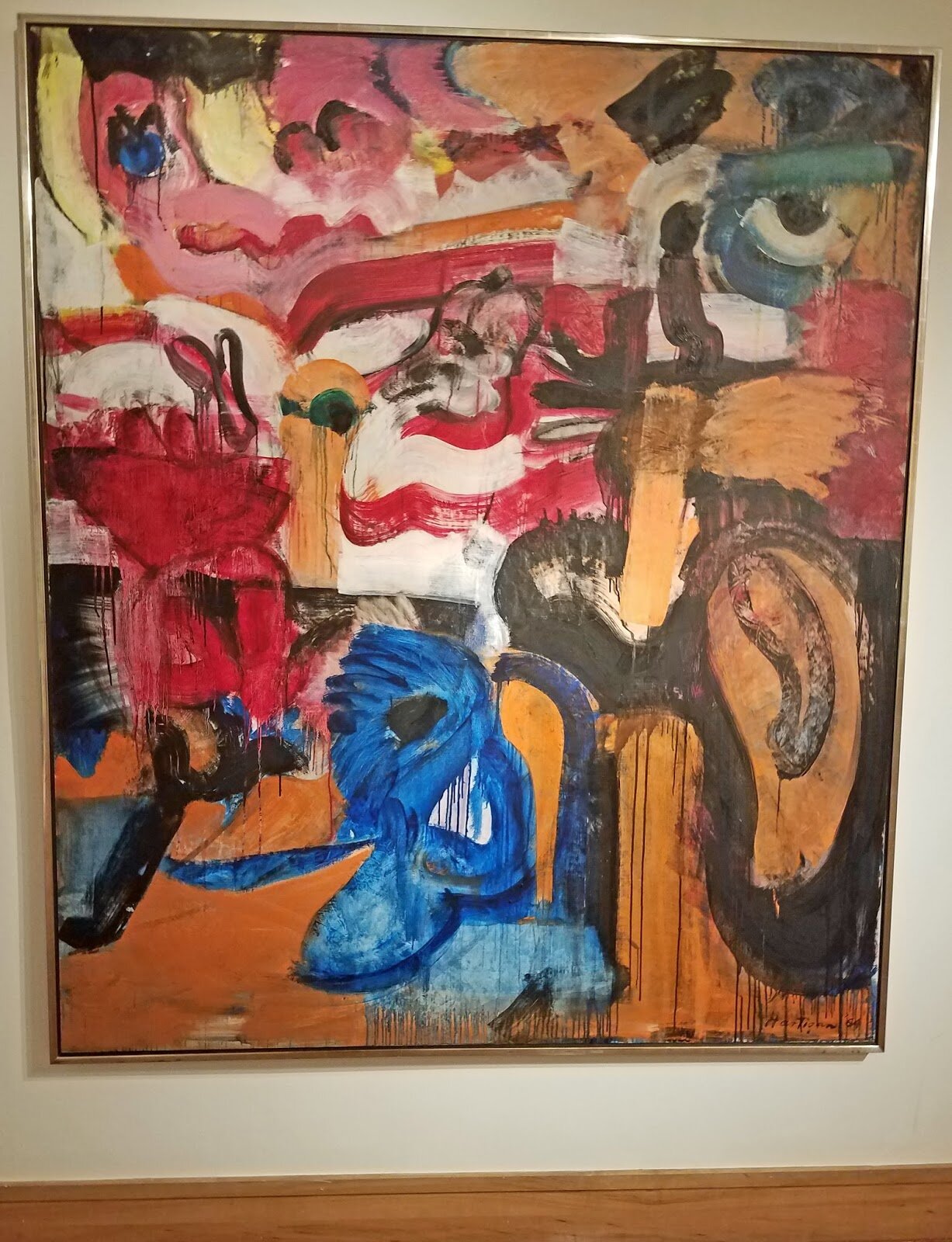

Opinion alert — Jackson Pollock is the most famous Abstract Expressionist painter. Fact alert — it was in New York City that Pollock and the other artists associated with this new movement blossomed. The “Irascibles,’ as they were dubbed, began to shake up the art world with their new philosophy and aesthetic. The novelty of Abstract Expressionism was powerful enough from the beginning to draw in a younger group of artists. Helen Frankenthaler, Joan Mitchell, Sam Francis, and Grace Hartigan are a few of the artists known as the second generation New York School. Despite her young age, Hartigan was deep in the Cedar Tavern circle and was considered a friend by Pollock, de Kooning, Rothko, Kline, etc. Curious and observant, Hartigan looked outward at her surrounding physical, social, and political world for inspiration. She began to paint a combination of what she saw and what she felt. Her commentary on daily life is the leading characteristic of her work. Her paintings such as Barbie have been interpreted as feminist precursors to pop art, but in reality, Hartigan did not ally herself with either feminism or pop art. For Barbie the output is a statement about the contemporary ‘60’s society. This painting and the great majority of her other works are musings on life and should be viewed the same way one reads poetry. A complete interpretation can only be accurately made by considering her own words as well as clues from her life’s story.

Hartigan was born on March 28, 1922 in New Jersey. She was greatly influenced by her aunt, an english schoolteacher who piqued her interest in writing and theatre which lasted all through high school. She married at age 18 and ended up in California after she and her husband ran out of money on their way to Alaska. They lived there several years with their newborn son until World War II broke out. They decided to move back east where he was then drafted. She began to take night classes to learn drawing and painting and got a job as a draftsman. She fell in love with Matisse after being introduced to book of his work and immediately began seeking out a way to paint like him. She then began to study under Ike Muse and moved to New York with him after she and her husband split. Not much time passed before she and Muse split also and she began to support herself with a “life of total poverty but meeting all marvelous, exciting people.”1 This is a reference to the collection of artists and writers who patronized the Cedar Tavern in the 40’s and 50’s. She visited Pollock’s and de Kooning’s studios and began the journey headfirst into pure Abstract Expressionism which solidified her status in the group as well as Clement Greenberg’s approval. Her first few works in ’49 and ’50 were very gestural and resembled the flat, all over composition of Pollock’s work. This only lasted a couple years before she began to slowly introduce representational elements that are very similar to the figures in de Kooning’s Woman paintings. A key factor in this change was her growing relationship with the poet Frank O’Hara. Hartigan’s childhood love for literature re-blossomed vicariously through O’Hara who dedicated several poems to her. In 1952 O’Hara gave a series of twelve poems called Oranges, Sweet, a Dozen to Hartigan who then turned them into her Orange paintings. This rebellion against Greenberg allowed her to extend her boundaries and begin to develop her own identity as a painter. Her first step was to look back at the Masters like Velasquez, Goya, and Rubens all the while keeping Matisse and the Abstract Expressionist aesthetic in mind. She then began to look outward in the exploration of her world, New York City. For several decades she painted shopping malls, billboards, vendors, shop windows, and anything else that caught her eye and stimulated her mind. Hartigan was overflowing with material that she felt compelled to paint. Throughout the ‘60’s she pulled out all the stops and painted everything from mythical creatures and gods, Marilyn Monroe, lily ponds, human emotions, and Barbie dolls. The only reoccurring visual elements are the gestural forms that came from her Abstract Expressionist background and the bold use of color drawn from her love for Fauvism. This inconsistency of subject matter is the first clue as to Hartigan’s thought processes.

The mistake that critics and historians too often make is the lack of attention paid to Hartigan’s body of work as a whole. When they step back and get the big picture view, they consider it for a couple of minutes and quickly conclude that, “She has reached for new ideas so often that she has no signature style.”2 Naturally at this conclusion, they are forced to focus on individual paintings or small series of them. Unsurprisingly, the interpretations of Hartigan’s Barbie paintings are straightforward and superficial.

The Barbie doll made her debut in 1959 and it was not long before Mattel, Inc. began receiving criticism for the doll’s negative body image. The doll has often been used as a symbol for the unacceptable image of women portrayed in pop-culture. When Hartigan painted Barbie in the heat of the controversy, many people, both feminists and non-feminists, assumed that she was making a feminist statement. The well-informed researcher might also argue his/her point with evidence that Hartigan originally signed her paintings as “George Hartigan” for her first few shows. This has been taken as a statement of the difficulty for women artists to succeed in the world of Abstract Expressionism. However, both of these arguments can be easily refuted by Hartigan’s own words. She has repeatedly denied having any feminist sentiments and even supported Pollock by saying, “The myth I find most infuriating is the one of Jackson Pollock as brawling, woman-hating, drunk and macho. The man was tender, suffering- an inarticulate, shy genius, but people don’t want to hear that about Jackson.”3 When asked why she signed her work “George Hartigan” she replied, “Because I identified with George Sand and George Eliot — they were my heroes. The real story is I had gay friends who all had female names amongst themselves and I thought it would be fun to have a man’s name.”4

The argument that Hartigan’s work is a precursor to Pop art has greater merit, but still doesn’t go much deeper than the paint on the canvas. Nevertheless, Hartigan did paint an abstract work titled, Billboard which can be compared to James Rosenquist’s work, and a couple of paintings of Marilyn Monroe which invariably conjures Warhol’s ghost. These images in addition to the Barbie doll are unquestionable pop culture icons. One can easily imagine Barbie as the subject of a Warhol painting and should not be surprised that he did indeed use the child’s toy in a series of prints. Warhol’s Barbie is very different from Hartigan’s however. In her essay, which analyzes Hartigan’s work, Melody Davis points out that, “Pop art is typically hard-edged, cool, acrylic-painted, repetitive and de-personalized.”5 This is the antithesis to Hartigan’s work. In response to this new aesthetic, she made an unapologetic statement in the 60’s saying, “Pop art is not painting, because painting must have content and emotion.”6 Similar to the contrast between the quality of a hand crafted table that exudes warmth from the carpenter’s personal touch and the mass-produced particle board piece made by machines and sold in an IKEA store, so is the unfriendly relationship of Hartigan and Pop art. It is not uncommon to see the subject of Barbie in everyday life, but just as Dutch genre painting is not Pop art, neither is Hartigan’s work.

Instead, the individual work is one of social commentary. Referring to the Barbie doll, Hartigan made this statement, “I’m very interested in dolls of all cultures, because a doll is an essence, really, of what society thinks you should present to your little girls, about what they’re supposed to plan for, how they’re supposed to think about themselves. And if you’re supposed to think about yourself as a bride that deserves a $100 dress and you only cost $15 and your husband is a castrated man, boy, that tells you something about American morals!”7 Hartigan painted what she saw around her. When she walked throughout New York City she painted vendors and shop windows. When she studied the masters at the MET she painted the scenes and figures that excited her. When she noticed a changing country she painted a doll that symbolized a part of it. Hartigan was not supporting or criticizing mass production, mass marketing, or mass media. She was taking input, processing it, and then giving output. Hartigan explains, “I try to declaw the terribleness of popular culture and turn it into beauty or meaning.”8 Now a motive fueling her creative machine becomes apparent. By zooming out and viewing the entirety of her life and work, we see that Hartigan takes both the ugly and mundane as well as the beautiful and exciting and gives them a poetic quality. This should not be a surprise, given her love for literature as a child, her very close relationships with the poets who patronized the Cedar Tavern (O’Hara in particular), and her “heroes,” the novelists Eliot and Sand. For the final piece of evidence let’s again consider Hartigan’s own words, “As most painting moves closer to sculpture and architecture, my own work moves nearer poetry…It increasingly must be ‘read’ in terms of meaning and metaphor.”9 Hartigan’s bold colors, gestural brushwork, and expression through abstraction are some of the tools she employs to give emotional life to the content that she chooses to paint. The successful viewer is the one who does indeed “read” her paintings. Poetry and Hartigan’s work are musings on life.

With a creative career that lasted over half a century, Hartigan produced a large body of paintings and prints. She did not stray far from her aesthetic, yet changes throughout the decades are visible and tell her life’s story like rings in a tree. Her experiences at the Cedar Tavern were truly invaluable and would cause envy in any historian. Unfortunately, she has been misunderstood a great deal too much. Barbie should be read as a poem, and not as Pop art or feminist art. Only then can one fully appreciate the creative mind of Grace Hartigan.

grace hartigan artist

Bibliography

Diggory, Terence. “Questions of identity in Oranges by Frank O’Hara and Grace Hartigan.” Art Journal 52, no. 4 (Winter93 1993): 41.Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed November 9, 2012).

Gibson, Ann Eden. Abstract expressionism: other politics. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997.

Hartigan, Grace, interview by Julie Haifley. May 10, 1979.

Hartigan, Grace, interview by Jonathan VanDyke. February 12, 2000.

Hobbs, Robert. 1995. “Grace Hartigan: A Painter’s World by Robert Saltonstall Mattison: Reviewed by Robert Hobbs.” Woman’s Art Journal , Vol. 16, №2 (Autumn, 1995 — Winter, 1996), pp. 42–44. JSTOR (accessed October 18, 2012).

Jachec, Nancy. The Philosophy and Politics of Abstract Expressionism: 1940–1960. Cambridge [u.a.: Cambridge Univ., 2000.

Kunitz, Daniel. “Gallery chronicle.” New Criterion 20, no. 3 (November 2001): 51–54. Art Full Text (H.W. Wilson), EBSCOhost (accessed October 19, 2012).

Landau, Ellen G… Reading abstract expressionism. New Haven: Yale, 2005.

Lavazzi, Thomas. 2000. “Lucky Pierre Gets into Finger Paint: Grace Hartigan and Frank O’Hara’s Oranges.” Aurora: The Journal Of The History Of Art 1, 122–137. Art Full Text (H.W. Wilson), EBSCOhost (accessed October 18, 2012).

Lord, M. G.. Forever Barbie: the unauthorized biography of a real doll. New York: Morrow and Co., 1994.

Princenthal, Nancy. 2009. “Grace Hartigan 1922–2008.” Art In America 97, no. 10: 142. Art Full Text (H.W. Wilson), EBSCOhost (accessed October 18, 2012).

Robert Saltonstall Mattison. “Hartigan, Grace.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed October 18, 2012,http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T036782.

Shapiro, David, and Cecile Shapiro.Abstract expressionism: a critical record. Cambridge [England: Cambridge University Press, 1990.